Serving Up the Basics of Tennis Scoring (And Why It’s So Weird)

Tennis scoring has mystified newcomers for ages. Why does “love” mean zero? What’s with the 15, 30, 40 progression? If you’ve ever watched a match and thought the umpire was speaking in riddles, you’re not alone. In this beginner-friendly guide, we’ll break down exactly how tennis scoring works, explore the quirky origins of the system, and share a few fun anecdotes along the way.

Game, Set, Match: Understanding the Scoring Structure

From Points to Games – How a Tennis Game is Scored

At first glance, tennis scoring seems nothing like counting. Instead of 1-2-3-4, you’ll hear “15, 30, 40, game!” during a single game of tennis. Here’s a quick rundown of how points translate into the score of a game:

0 points – “Love”

1 point – “15”

2 points – “30”

3 points – “40”

Tied score (each player has the same points under 40) – “All” (e.g. 15–all means 15-15)

40-40 tie – “Deuce” (more on this in a moment)

Point after deuce – “Advantage” (if you win the point at deuce, you have “advantage”)

Each tennis game is won by the first player to win at least four points and be at least two points ahead. For example, if you reach 40 and win the next point while your opponent has 30 or less, you win that game. However, if both players reach 40–40 (deuce), the game doesn’t end yet. From deuce, someone must win two points in a row to clinch the game. Win one point from deuce and you have “advantage”, but if you lose the next point, the score snaps back to deuce. This tug-of-war continues until one player wins two consecutive points, finally securing the game.

To make things a tad more interesting, when announcing the score the server’s score is said first. So if you hear “15–love,” that means the server has 15 (one point) and the opponent has 0 (love). “30–love” means the server won two points and the opponent none, and so on. If the server’s score is 0 and the opponent has e.g. 15, you’d hear “love–15.”

Games to Sets, Sets to Matches

Now that we know how points make a game, let’s zoom out. Tennis uses a hierarchy: points → games → sets → match. Here’s how it breaks down:

Games: As described, a game is a sequence of points. Win enough points (with a 2-point margin) to win a game.

Sets: A set is a collection of games. You need to win 6 games to win a set, but you must be ahead by at least two games. For example, 6–4 is a set win, but 6–5 is not enough. If the set reaches 5–5, you’ll have to win 7–5. If the set reaches 6–6, most tennis competitions use a tiebreak to decide the set 7–6. (The tiebreak is a special game using simple point counting 0,1,2,3… we’ll explain shortly and we have a full blog explaining this.)

Match: A match is won by winning the majority of sets. Most matches are best-of-three sets (first to 2 sets wins), though in Grand Slam men’s singles it’s often best-of-five (first to 3 sets wins).

And about that tiebreak: when a set reaches 6–6, players play a decisive tiebreak game (to 7 points, must win by 2). The tiebreak is scored with plain old numbers (“0, 1, 2…” instead of 15,30,40). The winner of the tiebreak takes the set 7–6.

In short: Win points to win games, win games to win sets, and win sets to win the match. Easy, right?

Love, Deuce, and Other Funny Tennis Terms

Why “Love” Means Zero

One of the first odd terms you’ll encounter is “love”, which, as we saw, means zero. Telling someone “love-all” at the start of a tennis game isn’t a sappy profession of affection, it just means 0–0. So why on earth use “love” for zero? There are a few theories (and sadly, no, it’s not because tennis is the game of love):

“For the love of the game” theory – The most popular explanation is that players with zero points are still playing for love of the game rather than for points. In other words, even if you haven’t scored, you’re still out there giving it your all because you love playing.

French “l’œuf” (the egg) theory – Another famous story traces love to the French word l’œuf, meaning “egg,” supposedly because an egg looks like a 0. According to this tale, English players misheard or mangled l’œuf into “love”. It makes for a fun legend (and a mental image of an egg on the scoreboard), but linguists haven’t found evidence that French players actually used “egg” to mean zero in tennis.

Honorable origins – A less common theory suggests “love” comes from the Dutch or Flemish word lof, meaning honor. If you have zero, you’re playing on for honor. This one is more obscure, but historians note that in gambling or wagering contexts, playing “for love” meant playing for nothing. That aligns with the idea that at 0 points, a player is effectively playing for nothing.

Deuce, Advantage, and “All” – The Language of Ties

Besides love, tennis has other unique lingo when players are tied or nearing the end of a game:

All – When both players have the same score below 40, we say “all.” For example, 15–15 is “15-all.” It’s a straightforward term indicating an even score.

Deuce – When a game reaches 40–40, we enter deuce. Deuce essentially means “tied at 40, need two consecutive points to win.” The word comes from French deux, meaning “two”, since from 40–40 you need to win two points in a row to take the game.

Advantage – The point after deuce is called advantage (or “ad” for short). If you win the point at deuce, you have “advantage.” If you win the next point as well, you win the game. If you fail to win that next point, the score returns to deuce.

These terms can feel odd at first, but they add to tennis’s charm. There’s something dramatic about hearing “deuce” in a tense game. And if you’re wondering, why not just call it 40–40 and then 50–40, 50–50, etc? Good question! The short answer: tradition. Which brings us to…

A Trip Through Time: Origins of the Tennis Scoring System

Tennis scoring didn’t come out of nowhere; it evolved over centuries. To appreciate why we count this way, we need to travel back in time to medieval Europe, when tennis was the game of kings and commoners alike.

Medieval French Roots – Jeu de Paume and 15-30-40

Modern tennis traces its roots to a French game called jeu de paume (“game of the palm”) played in the 12th-16th centuries. Back then, players hit the ball with their bare hand, and later with primitive racquets. The scoring system used in those days will look familiar: historical records show scores counted as 15, 30, 45. In fact, one 15th-century poem recounts a tennis game with the score moving from 15 to 30 to 45. So the concept of counting by 15s per point was around over 600 years ago!

Why 15 points per score? We’re not 100% sure. Even a 16th-century observer mused, “Why is it that players can win fifteen points for a single stroke? Why not one point for one stroke?” Over the years, a few interesting theories have been proposed:

The Clock Face Theory – Many believe the scoring came from a clock dial. Imagine a clock face as the scoreboard: start at 0, then a quarter turn for each point – 15, 30, 45, and when the hand completes the circle at 60 that would be the game. According to lore, when clocks weren’t used anymore, 45 was shortened to 40. Skeptics note a historical snag: mechanical clocks with minute hands weren’t common until later in the 16th century. So if tennis scoring predates that, the timeline might not add up.

The Court Geometry Theory – Another neat theory ties scoring to the layout of medieval courts. One version goes like this: a jeu de paume court was about 45 feet long on each side. Each time a player scored, they could move up 15 feet closer to the net, starting from the backcourt, first to the 15-foot line, then to the 30-foot line, then to the 40-foot line. In other words, 15, 30, 40 corresponded to how far forward you could move after each point. If true, this would make the scoring very literal, it measured court position gained.

15 Points = 1, 2, 3? – It’s also possible that using 15, 30, 45 was just a way to represent a simple count of 1, 2, 3 using larger units (15 being a nice round number). In an era when much of the world used base-60 counting (think 60 minutes in an hour), increments of 15 might have felt natural. And why was 45 truncated to 40? Perhaps to avoid confusion or simplify the math of needing two more points (45 + 15 would overshoot 60). One suggestion is that saying “forty-five” (three syllables) was a bit unwieldy compared to “fifteen” and “thirty” (two syllables each), so players started saying “forty” for ease. It might have just been an informal change that stuck over time.

The truth is, no one knows for sure why these numbers were chosen. The system was already considered mystifying centuries ago. But these legends and theories are part of tennis’s rich lore.

Sticking with Tradition – Why the Scoring Stayed Weird

By the late 19th century, lawn tennis adopted this quirky medieval scoring wholesale. In 1877, the very first Wimbledon Championship used the 15-30-40 system, resurrecting it from the old royal tennis rules. Ever since, tennis has largely stuck with it. But not everyone was thrilled. In the 1960s, some officials actually blamed the complex scoring for tennis’s dip in popularity in certain places. One even quipped that perhaps the tennis authorities would “fall out of love with love” and simplify the scores. (Gotta appreciate the pun!) Needless to say, love (meaning zero) survived that scare.

Over time, a few tweaks have been made in the name of practicality. The biggest was adding the tiebreaker in the 1970s, so that sets wouldn’t go on forever. Traditional scoring without a tiebreak could, in theory, continue indefinitely until someone leads by two games. Other experimental scoring systems (like “no-ad” scoring where deuce is sudden death) have been tried in some leagues to speed things up, but the classic system is still the norm in professional tennis.

Fun Anecdotes and Oddities in Scoring

When Scores Go Wild – Marathon Matches and More

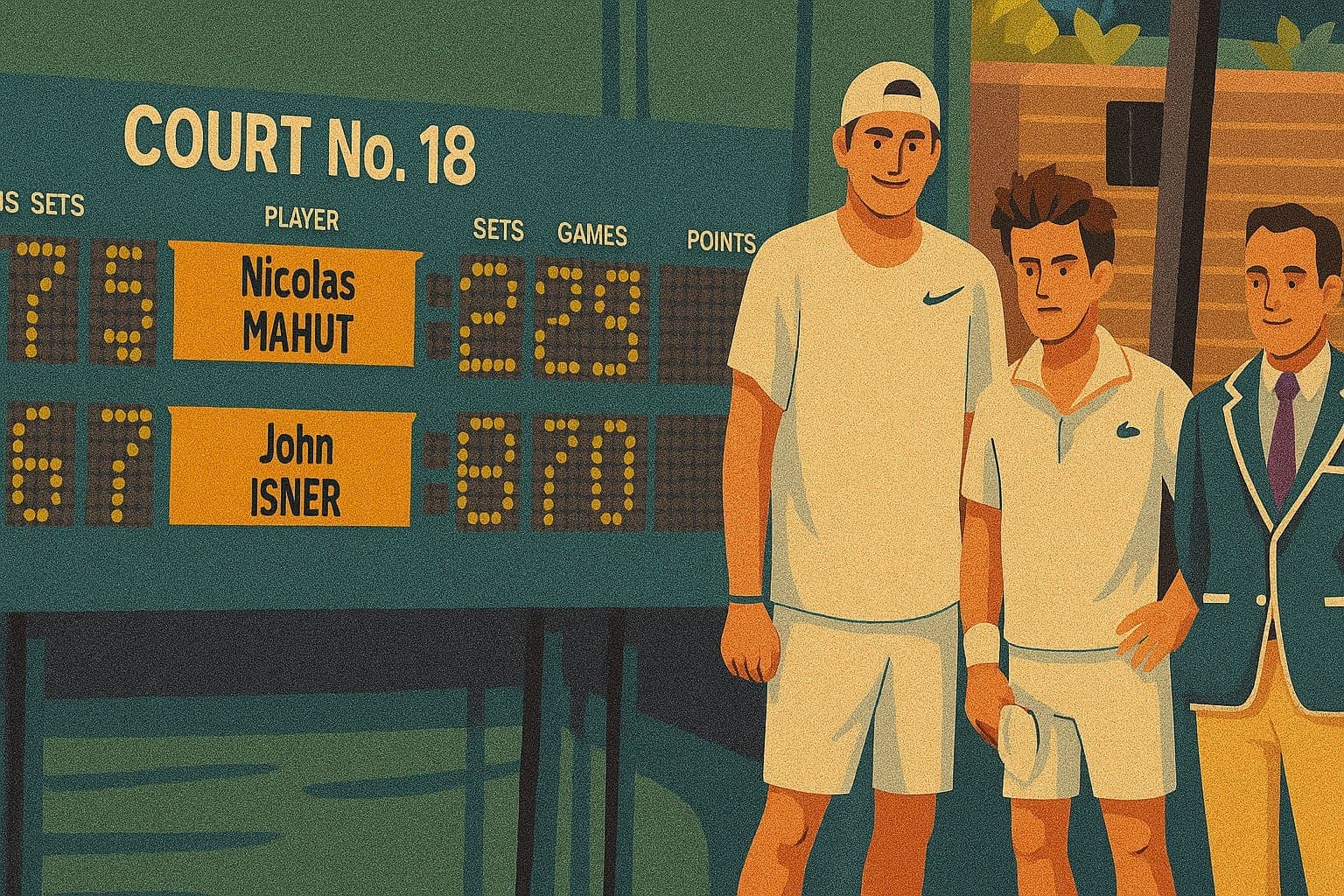

Most of the time, tennis scores stay within a pretty normal range. But every now and then, the traditional scoring system produces some eye-popping numbers. For instance, before final-set tiebreaks were standard, players could end up in seemingly endless duels. The most famous example? John Isner vs. Nicolas Mahut, Wimbledon 2010. These two played a match so long it had to be spread over three days. The final set alone stretched to 70–68 in games! After 11 hours and 5 minutes of play, Isner won that epic fifth set 70–68. The scoreboard actually broke at 47–47 and had to be fixed overnight. This historic battle eventually prompted rule changes: today, all Grand Slam tournaments use some form of deciding tiebreak to cap these marathons.

And here’s a charming fact: “love” has cousins in other sports. Some card games and other racket sports also use “love” for zero. So tennis isn’t the only culprit of quirky jargon, it’s just the most famous.

Embracing the Quirk – Why We Love Tennis Scoring

Despite all its weirdness, tennis scoring has a special place in fans’ hearts. It’s a piece of history we interact with every time we play or watch. There’s a certain delight in hearing an absolute beginner ask, “Wait, why did the score go from 30 to 40 instead of 45?” and getting to share the colorful theories. It becomes an anecdote.

Ultimately, the strange scoring is part of tennis’s identity. Just as golf has birdies and bogeys, and baseball has its strikes and balls, tennis has its loves and deuces. It may seem baffling at first, but as you grow familiar with it, you might start to find it endearing. And when you finally explain it to the next newbie, you’ll do so with a bit of pride.

Bottom line: Tennis scoring is weird, no doubt. But it’s also wonderful. It connects today’s game to its rich history, it gives the sport character, and it adds an extra layer of excitement (who doesn’t feel their heart pump a bit faster at deuce in a tiebreak?). So the next time someone asks why tennis can’t just count normally, you can wink and say, “Where’s the fun in that?”

Ready to Play? Put Your New Knowledge into Action!

Practice Makes Perfect

Now that you’re equipped with the knowledge of how tennis scoring works and the legends behind it, the best way to truly get comfortable is to experience it—and if you’d like a little expert guidance, your first lesson at TMT is totally on us. Grab a friend, a couple of rackets, and a fuzzy yellow ball, and try playing a few games. Call out the score loud and proud—“15-love!”—and don’t worry if you slip up or have to think about what comes after 30 (it’s 40, we promise). With a bit of practice (and perhaps that complimentary session with one of our friendly coaches), you’ll be keeping score like a pro, and the strange terms will start feeling second nature.

Ready to serve up some fun? Book your first free lesson with TMT today, and let’s hit some aces together. Game, set, match—and an amazing tennis journey—await you. See you on the court!